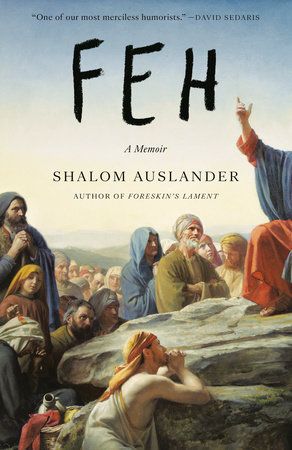

The Story and Stories of Feh, or: Stories of the Story of Feh

Aug 11, 2025

It's not a stretch to say that Shalom Auslander's Feh: A Memoir is a book about the messiness of being human.

At the core of Feh are two threads wound tightly around each other. The first, and the driver of Auslander's narrative, is the story of a handful of recent years in Auslander's life, wherein he has struggled.

Struggled is an understatement.

Auslander struggles with his weight and with his self-image. He struggles with his value as a writer, with a sense of being a fraud. He struggles with the career choices he made that led him to be effectively unemployed, attempting and largely failing to write for Hollywood. He struggles with the sense that he has let everyone around him down, especially his family. He struggles during COVID.

He struggles, and in navigating the struggle he reaches for a range of obvious and less-obvious self-destructive behaviors, from various sorts of semi-legal drug use to pushing away those closest to him.

It is an often heartbreaking memoir that can be a bit difficult to read at times. Anyone who has struggled with issues of confidence or self-image knows some of the feelings Auslander shares here. Auslander's inner voices, turned inside-out for all to witness, sound familiar. They also know the self-deprecating humor that comes with such struggles. That's here in abundance, too. Auslander is quite funny with an untamed imagination and a dry, occasionally crude, frequently curse-laden wit. It makes some of the heartbreak and downward spiral feel less overwhelming, but when he turns that voice on himself -- again, if you've struggled with these feelings, you can feel the sting because you recognize it.

If this was all Feh was - an account of depression and finding a way through it, laced with a steady drumbeat of self-deprecating humor - I probably wouldn't be writing about it.

But Feh is also a memoir about stories. In particular, Auslander is interested in the stories that tell us over and over again that we are unworthy and gross, that humanity is nothing but awful and that we, as specimens of the species, have no choice but to represent that awfulness to the fullest. The pessimistic stories. The cynical stories.

He boils this down to a master story: the story of feh.

There is a wonderful error in the auto-transcription of the linked video, which reads: it's a word that sounds like how you emote the feeling of faith. I love that error as I am not sure it's entirely wrong.

Feh is of course a Yiddish word, defined in the book's front matter as "an expression of disapproval or disgust." There's something onomatopoeic about feh; as someone on this video panel says, "It's a word that sounds like how you emote the feeling of feh." So take a moment to hear it from the lips of James Cagney, with gusto.

From the very first chapter, Auslander highlights what he calls the story of feh, a story, he says, that we are told, unceasingly, from day one. He recalls his time at an ultra-Orthodox yeshiva, when he is a child, hearing the story of creation. He tells of this moment by telling a story of his own. Reimagining the creation stories of Genesis, he finds god pulling up a stool to talk to Gabriel, who is a bartender, after Cain has killed Abel. Humans are feh, god says and Gabriel concurs, "from top to bottom. Totally, irredeemably feh."[1]

This story, Auslander suggests, is the foundation of so many of the stories we are told about ourselves, so many of the stories that we learn to tell ourselves about ourselves. This is the second core thread of Feh. In addition to a memoir, Auslander is tracing these stories in different forms, exploring how they engage with the master narrative of feh.

Although he has a special animus toward the religious versions of this story, Auslander finds feh just about everywhere. We are treated to readings of writers like Kafka and Raymond Carver, or philosophers like Schopenhauer and Pascal, Rousseau and Hobbes. There are exegeses on more abstract stories, like the stories of capitalism, the stories of Victoria's Secret and of Penthouse Variations, stories about women and about gender and sexuality. The Bible was already secure in Auslander's canon as Feh I. When Auslander learns that Atlas Shrugged was second only to the Bible in a list of books Americans had identified as influential in their lives, he calls it Feh II.

For Auslander, all of these stories are either variations on the story of feh or, in some cases, deconstructions or lines of flight from that story. Auslander literally rewrites these stories, meaning that Feh is full of concise retellings of famous narratives. Many of these retellings are quite good in their own right, funny and often insightful.

Here's his take on Carver's "A Small, Good Thing":

SPLAT

Once upon a time there was a little boy. His birthday was coming up, so his mother planned a party. She ordered him a cake. Everyone was excited.

The morning of his birthday, the little boy got T-boned by a car.

Splat.

Later, he riffs on Carver's 'Popular Mechanics' and calls it 'Split.'

Auslander draws on the backstory behind "A Small, Good Thing" to connect this back to feh. Gordon Lish famously cut off the end of the story, which did not originally end with the crushing of the boy but with grieving parents working their way through that grief. Auslander sees in this anecdote two dueling narratives:

Carver wanted to tell a story about getting through the darkness, about seeing the good in life and each other. [...] Lish wanted to tell a darker story. A story called Life Sucks and People Suck, So What's the Point?, a story we all, living and dead, Eastern and Western, have been told a thousand thousand times, in a thousand thousand forms, a cancer-like story we have internalized as a species and believe without question. A story called Feh.[2]

This depiction of dueling stories gets close to the heart of Auslander's effort here. In tracing these stories, their shape and their virality, he wants to learn how to make room for other stories.

He tries to do this for his children, for instance, giving them the space to learn about themselves without judgment or ridicule -- without a pronouncement of feh.

He especially finds a great amount of comfort when he starts hanging out at a coffee shop run by a pastor who has the wild idea that everyone is worth feeding and taking care of. The coffee shop has no prices, people pay what they want or they can, and folks who need food can get it. Auslander sees people being treated with dignity and compassion no matter who they were or what they were struggling with. He starts writing there and finds some community.

He finds in these words from Chimamanda Adichie's "Danger of a Single Story," a concise version of his project:

I would like to end with this thought, that when we reject the single story, when we realize that there is never a single story about any place, we regain a kind of paradise.

Every now and again, Auslander spies that paradise. Peeking through the darker moments of his memoir, Auslander lets some of that light in, even if he doesn't always understand where it comes from or how it works.

Even if we want to, it's hard to get away from stories that essentialize humanity as nothing but mess. They operate on our impression of humanity as a whole, humanity as individuals, and humanity as we represent it in ourselves.

We don't just hear these stories either. We make them and spread them ourselves. Think for a moment about how casually we write off others in our species. Memes tell us that all humans are awful and we laugh. We half-joke (but barely, not really) about how much we avoid other people - by phone, in person, every modality really - and we take to social media to chronicle all the petty annoyances that we experienced from other humans on public transport, at the grocery store, in traffic. We have learned to use some very impressive technological achievements to amplify the worst of humanity, in ourselves and in our neighbors and in total strangers, near us and on the other side of the globe.

Of course, there is no shortage of texts that show and tell us how humanity has, throughout written history, often despised itself, and how frequently we have sought to get away from ourselves. But I don't think it is far-fetched to see in our time a real penchant for the 'most humans suck' mood.

Ours is not an age of grace or patience or humility. Certainly not to others and often not even to ourselves. It is, however, an age of fear and cynicism, where even the acts that might model the best of us can be ruthlessly deconstructed into a symbol of the worst of us.

In this sense, Auslander's call for more stories connects with me, particularly for stories that embrace humanity's messiness and counter the story of feh.

But whether he recognizes it or not, Auslander is also showing us something else in Feh: the power of interpretation, of exegesis. New stories are great, but there's something valuable in taking apart old stories, too, and understanding them in new ways. That's a big part of what Feh does. Auslander doesn't just point to a Carver story or the book of Job and say, "See, there's a story of Feh." He gets into the story, he looks at it from different angles, he retells it by picking at or exaggerating its gaps and omissions.

At points, this aspect of Feh reminded a lot of the best examples of midrash, which can be quite imaginative and even playful. And although he often pronounces a story to be basically a story of feh, he occasionally hints at other ways we could look at a given story.

Despite all the re-interpreting that he is doing throughout the book, Auslander doesn't ever address this process of interpretation and re-interpretation. The impression is that stories, for Auslander, are vehicles of one-way communication. The story of feh, in its many forms and variations, gets delivered to us. We learn its message, we absorb it, we replicate it and distribute it to others. And the story of feh, for Auslander, always seems absolute and flat, a fiat.

There's a whole host of interesting questions that pop up if we question this narrative of narratives, some of which could really resonate with Auslander's project. A few come to mind:

- If stories allow for a plurality of meanings, why is the story of feh so persuasive and successful?

- To what extent can the story of feh co-exist with other stories that challenge its view of humanity?

- Or, if the story of feh is so apparent in some aspects of the Bible, how and why have people also found in its texts the very opposite message?

Consider this last question.

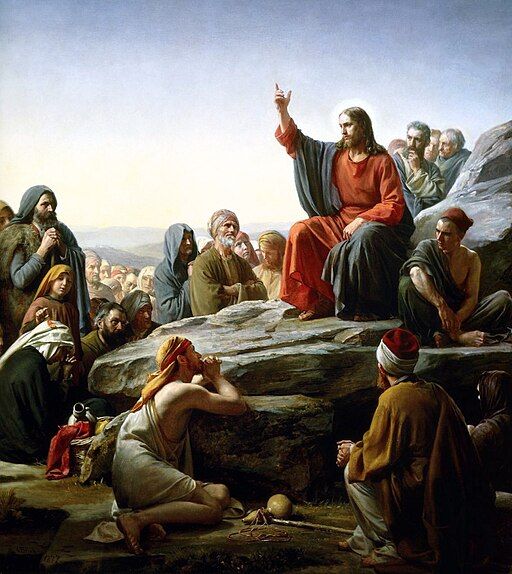

Towards the end of Feh, Auslander zooms in on a painting, The Sermon on the Mount, by a Danish artist named Carl Bloch, in which Jesus seems to be addressing an attentive crowd. Auslander zooms in one man in the scene, the only figure who seems more taken with a small child playing than with Jesus and his preaching. Auslander finds a line of flight in that man, a possible escape from the scene as it is normally interpreted, a man possibly "turning his back to Jesus." This painting is very identifiable, certainly one of the most commonly used illustrations of Jesus since it was created. And here, Auslander has found a minor but possibly profound retelling of the painting by honing in on a particular individual, one who seems set apart from the crowd.[3]

It's a smart catch.

But Auslander never addresses that the painting is of the Sermon on the Mount. Auslander casts Jesus as "judging" in the painting, but the Sermon on the Mount is probably the one portion of the gospels that is most explicitly aligned with Auslander's desire for stories of human dignity. To the extent that he is judging, Jesus is judging humanity for its poor treatment of the weak, the poor, the persecuted. But my guess is that, if the pastor who runs the pay-what-you-can cafe were to list a set of scripture references that has inspired his particular understanding of how to act in the world, there's a good chance he'd point to the very passage this painting is built around.

That does not invalidate Auslander's observation or even his interpretation. If anything, it opens up some new possibilities.

From Madeleine Thien's The Book of Records:

"How much can a person learn with three books?" Blucher mused, picking up Volume 84.

"Each volume is a square of time," replied Bento. "Hundreds of mornings."

"And each morning is a universe," Jupiter said. "What's that saying again? 'Heavy is the root of light.'"

As if I were a pebble on the shore, I felt myself, bit by bit, dislodged by their words. Blucher picked up the story and continued.[4]

Auslander, Feh, 5. ↩︎

Auslander, 182-183. ↩︎

Painting is Carl Bloch, "Sermon on the Mount," Public domain via Wikimedia Commons. ↩︎

Thien, The Book of Records, Chapter 6, p. 91. ↩︎